Books+ Spring 2023

My one new year’s resolution for 2023 was to read more poetry. Or, read poetry, period. I like the practice of reading and then re-reading short snippets of raw emotion in bed at night. It makes for rich dreams. I also read a lot of the current best sellers, because why not?

—

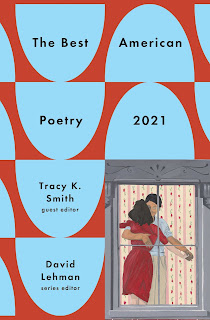

The Best American Poetry 2021, Tracy K. Smith, Guest Editor & David Lehman, Series Editor

Anthologies are always interesting reflections of the mood of a culture at a particular moment. This book is no different. A lot of the poems reflect the rawness and desperation of the Left during the summer of 2020–this is a decidedly blue book. Today, the explosion of pent-up rage and hope during that summer already feels distant and a little unreal. This anthology will transport you back to the moment’s aftershocks.

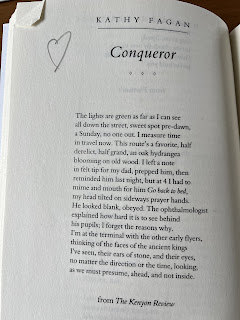

My favorites:

Weaving Sundown in a Scarlet Light: 50 Poems for 50 Years by Joy Harjo

Many people have written far more informed analyses of Joy Harjo’s long career. What I can say about our 23rd Poet Laureate’s work in this collection of poems is that she has a commitment to seeing and healing darkness with beauty. When I was growing up, my parents had a collection of invective Soviet (translated) poetry by a woman whose name I never learned. That was my initial understanding of poetry—well, that and British children’s chestnuts. Harjo’s work is the opposite of the anger and sloganeering that burned through those old pages from the USSR. Her poems feel like the equivalent of healing trauma with a long, quiet walk through the wild world, foot to earth, forehead to sky.

An example:

Hell Bent by Leigh Bardugo

It’s rare that a sequel is better than the first of a book series, but Bardugo managed to do the near impossible with this book. Ninth House was good but also confusing in parts; it felt like it could use some editing. Hell Bent is sleek and fun but doesn’t give up the delicious darkness of the first book in the series. The main character wants to go to hell—sounds about right.

When No One Is Watching by Alyssa Cole

Cole’s book feels like a script of a limited series Netflix show: white people are rapidly moving into the main character’s neighborhood in Brooklyn, and her black neighbors are disappearing under mysterious circumstances. It’s a gentrification horror story meets revenge porn set against a vivid, hot Brooklyn summer setting. Would this book have been published before 2020 with the ending intact? Probably not.

Carrie Soto Is Back by Taylor Jenkins Reid

Reid’s sharp romp through the professional tennis circuit is a good time even if you don’t find tennis all that interesting. The main character, a superstar tennis player of the ‘80s, comes out of retirement at 37 to defend her record against an upstart. The story is fun not because of any intricate plot, but because Reid writes Carrie and her nemesis as unapologetically aggressive and determined to win.

Tomorrow And Tomorrow And Tomorrow: A Novel by Gabrielle Zevin

Culture writers seem to be waking up to the reality that most Americans are far more interested in video games than opera, theater, books, or even popular music; my son’s favorite music is determined by the games he’s playing at the moment, but there’s no Grammy category for that. So, this book about the complicated relationship of two gamers over a few decades seems novel to people who don’t spend a lot of time gaming. But I suspect this would seem par for the course to most Americans under 25. Part of the book is written in one of the games. The emotional arc of the main characters is not especially poignant despite best attempts, but the premise and game worlds are immersive and nostalgic.

The Body Keeps Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel Van Der Kolk, M.D.

I read popular science books with a grain of salt on my tongue, particularly best sellers. The ideas are popular because they resonate with something deep in humans—in this case, a sense that our bodies are carrying a lot of trauma after a particularly hard stretch of years. But I also remain neutral about the truth of such books unless I take the time to read the scientific papers that underly their claims. I have not done any such thing with this book, so I still have no idea if anything Van Der Kolk says is true. But his essential argument that humans store trauma in our bodies and minds, and that efforts to heal this trauma—and particularly childhood trauma—has to engage both the mind and body, seems (?) common sense.

I’ve been more aware of the somatics of emotion over the last few years. In my one attempt to try acupuncture last year, the first needle went in and out flooded a wholly unexpected emotional experience from the past. What was that about? I’ve been keeping this framework in mind as I work through some of my own old stuff in personal therapy these days. How do I mourn things that happened in the distant past? It certainly won’t be by sitting still and just thinking.

Time To Think: The Inside Story of the Collapse of the Tavistock’s Gender Service for Children by Hannah Barnes

A large portion of The Body Keeps Score is about the lingering, somatic trauma of children who have been through horrific experiences. Barnes’s book also discusses the treatment of children who, in many cases, are struggling with a host of especially difficult, and sometimes similar circumstances and are disconnected/at war with their bodies. And like Van Der Kolk, Barnes documents how a purely medication-based approach to helping kids with these complicated circumstances too often did not deliver what these kids needed. It’s interesting to read these books back-to-back because they reflect such profoundly divergent ways of looking at how to help children in desperate need of care. Whether or not you think the fundamental approach of the Tavistock is correct (follow the links and read the underlying science to make up your own mind), this book is a sobering look at good intentions gone wrong—and the children caught in this vicious spiral.

Barnes’s book transforms the independent report and court cases about the institution that have informed the British government’s decision to close the Tavistock clinic and reimagine pediatric gender care into a compelling narrative (again, check out the footnotes and decide whether you think this is an accurate account for yourself). But I do wish that Barnes had spent more time talking about the Tavistock clinic’s history of gay conversion therapy, and how that experience influenced the institution’s approach to its pediatric gender services. Barnes briefly touches on this toward the end of the book, but it seems worth digging in more. There is a huge swath of people who are—rightly—extremely wary of subjecting anyone to the equivalent of the cruelty and pointlessness of gay conversion therapy and other expressions of homophobia; we want to have learned our collective lesson and do better when it comes to gender. Yet the sources that inform this book strongly suggest that we know less than we think we do about gender and gender care. Not asking questions is not the liberatory path, particularly when children are involved. That, surely, is one lesson we can learn from the darker past.

Galileo’s Middle Finger: Heretics, Activists, and One Scholar’s Search for Justice by Alice Dreger

I worked as a professional transportation and land use advocate for roughly 10 years of my career and have been a volunteer advocate on various issues, including police reform and public schools, so the term advocate has been a big part of my identity for most of my adult life. I have been the outsider, the too radical and uncomfortable presence trying to get a seat at the table; I, too, have banged my head against the wall about consistently, and infuriatingly biased press coverage.

So, it was an interesting experience to read about the role of advocates in both Galileo’s Middle Finger and Time To Think. My instinct is to see all the many complex stories in these books from the perspective of the various advocates. I know how incredibly hard it is to get anyone in power to give two figs about your issue, even when people are dying. And even when the people opposing you don’t even pretend to be civil.

But two of the key responsibilities of an effective advocate are 1) to stay grounded in your complex humanity and 2) know when your own sh*t stinks. You can’t do one without the other. Dreger’s passionate book tries to triangulate the healthy role of advocates, science, and media, from the perspective of a woman who has toggled between advocacy and science throughout her life, and these themes emerged time and again. I found myself nodding as she diagnosed the particularly difficult situation we’re in right now with the collapse of a reliable and truly inquisitive fourth estate. After all, there will always be inconvenient truths on the path of liberation; they help us hone our core values and discern the integrity of the possible paths ahead. But that process is slightly easier when advocates, scientists, and the media are all doing their jobs with probity.

Dreger in her own words:

“So long as we believe that bad acts are committed only by evil people and that good people do only good, we will fail to see, believe, or prevent these kinds of travesties.”

-Galileo’s Middle Finger, p. 275

“If we now combine the loss of a vigorous free investigative press with the loss of freedom of inquiry in our universities, who will be left to find out the truths that must underlie our social policies, our justice system, our health-care practices? Who is going to be left to do the hard work of democracy?” -Galileo’s Middle Finger, p. 276

Spare by Prince Harry

Why not? I watched The Crown last year, which tries to be as sympathetic to all the royal family members as possible, but also makes clear what a twisted, lost man Harry’s dad is along with everyone else. This book doesn’t disabuse readers of that notion, and suggests that Harry’s brother is also lost in his own navel, or worse. It’s a thoroughly uninspiring line of succession. Assuming this is all true, I can see why Harry would want to find a new life. Though I can also see why the press is eager to continue to mine the family for its cultural pageantry and dysfunction; it’s the oldest reality TV show running, with poison pill contracts for the talent.

White Lotus, Seasons 1 & 2 from HBO

Oh, the lush settings, cinematography, and perfectly aggravating and clueless characters (though the brilliant Natasha Rothwell was tragically underused)! I especially loved the scene cuts in the “Bull Elephants” episode of Season 2. The jet ski scene juxtaposed with the dialogue was a chef’s kiss. Rest in pino, Jennifer Coolidge.

—